In the spring of 2007, Simone Fontanelli, a world renowned composer and professor of new music at the University of Mozarteum in Salzberg, gave a series of seminars at the University of Georgia, Dancz Center for New Music. I asked maestro Fontanelli, “are there any composition exercises you would recommend to help beginning composers develop their own voice?” He suggested borrowing harmonic, melodic and/or rhythmic ideas from three great composers, then write a new piece which combines the best elements of all three. For example, combine Stravinsky’s Petrushka chord, Bartok’s rhythmic motives from String Quartet No. 4 and Schoenberg’s concept of developing variation into a single composition. This is challenging to say the least, and it stretches the abilities of most composers. In addition, this exercise gives beginning composers an opportunity “walk in the shoes” of the world’s greatest composers, thereby, discovering what makes them great. It also helps beginning composers get into the historical flow of what has gone before them.

This idea is not new. All great composers have written pieces “in the style of…” For example, Mozart was influenced by Bach, Haydn and many others. Schoenberg considered himself to be an extension of the German tradition and was influenced by Bach, Beethoven and Brahms.

While working on my DMA in music composition at UGA, I read a number of interviews with György Ligeti (1923-2006), one of the most influential composers of the 20th century, in which he discussed the influence of Bartók on his compositional style and technique. Ligeti used Bartók’s String Quartet No. 4 as a model when he wrote String Quartet No. 1: Metamorphosis Nocturnes (1954). In fact, in an interview with Friedemann Sallis, Ligeti stated he knew Bartók’s style so well that “he could have gone on to write the seventh, eighth or even twelfth Bartók quartet.”

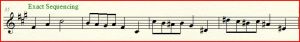

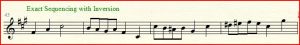

I decided to analyze both quartets to determine if this statement is true and, if so, discover what elements of Bartók’s quartet and style are present in Metamorphosis Nocturnes. It appears that Ligeti borrowed a motive directly from Bartók’s quartet, see Example No. 1. This motive belongs to set class [0123]. Ligeti uses it in the beginning of Metamorphosis Nocturnes, and it becomes the primary harmonic structure throughout the entire quartet, see Example No. 2. It is interesting to note, after writing Metamorphosis Nocturnes, Ligeti continued to use set class [0123] throughout his career, but he added his own twist in the form of microtonality.

Example No. 1

There are a number of parallels between these two quartets, and Bartók’s influence is present throughout to the extent that Ligeti’s quartet sounds more like Bartók than Ligeti. With that being said, Metamorphosis Nocturnes is a model for all aspiring composers. Ligeti wrote his quartet in order to experiment with Bartók’s harmonic and melodic language. He ultimately kept what he liked most from Bartók’s style, eventually making it his own. In the process, he developed his own unique voice. March 20-23, I will present my research at the 2014 Society of Composers Inc. Nation Conference at Ball State University in Indiana.

I would recommend trying the same experiment with your own favorite composer or composers. Borrow a melody/harmony or two. Take it out for a test drive. If you like it, find a way to make it your own!